Los Angeles

We dropped off our car at Los Angeles Airport and took a taxi to the Hotel Roosevelt in Hollywood. This was a special treat for us. When we were last in LA in 2001, we fell in love with the foyer of the Roosevelt and vowed that we would one day stay there.

The Hotel Roosevelt has an impeccable Hollywood heritage having been founded by a syndicate made up of Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Sid Grauman (of Grauman’s Chinese Theater fame) and Louis B. Mayer (The last “M” in MGM). And that was just the beginning. The hotel hosted the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929. A few years later, a young Shirley Temple would learn how to tap dance from Bill “Bojangles” Robinson on the hotel’s staircase. Norma Jeane Mortenson would have her first commercial photographs taken at the the hotel. These photographs would in turn be seen by 20th Century Fox executive Ben Lyon who invited Mortenson for a screen test. Lyon loved her and signed her up on the spot but insisted that she change her name to something more marketable. Lyon thought she looked like the old 1920’s Ziegfeld Follies star, Marilyn Miller while Mortenson herself suggested her mother’s maiden name of Monroe. Thus Marilyn Monroe was born. Bizarrely, Marilyn Monroe would technically (in those pre-liberated days) become Marilyn Miller when she married playwright Arthur Miller.

The hotel has a classic twenties decadence to it and has been recently renovated to maintain its prestigious reputation. Part of that prestige can be found in The Spare Room, the hotel’s prohibition-style nightclub and gaming room that has a beautiful old wooden bowling alley. Our hotel room was very nice and made more so for its view over Hollywood Boulevard where, much like Times Square in New York, things were happening all day and night.

Marilyn Monroe posing on the diving board at the The Roosevelt Hotel in her first modelling photograph (for Tar Tan suntan lotion). The pool now sports an underwater mural by David Hockney.

Warner Brothers Studios

What’s a trip to Hollywood without visiting a studio or four? Our first tour was to Warner Brothers Studios in Burbank.

The studio really should be called Wonskolaser Brothers Studios after the proper surname of the the four founding Jewish brothers from Poland. Prior to getting into the new craze of moving pictures, Harry Wonskolaser and his brothers had sold and repaired shoes, ran a bicycle shop, sold meat goods and managed a bowling alley.

Like many immigrant Jews, they felt the need to Anglicize their name in order to fit in with mainstream America. Thus Wonskolaser became Warner. And also like immigrant Jews, they loved the fact that the new motion pictures being cranked out of New York didn’t require a proficiency in English to be understood and enjoyed by people like them. I remember Lilian Gish’s great quote from the superb Brownlow and Gill Hollywood TV series, where she described silent movies as “an international pantomime language capable of being immediately grasped by audiences anywhere.”

The Warner brothers were canny businessmen and pretty quickly worked out that these new movies would result in big money. After all, they were cheap to make, cheap to see (the theatres that showed them were even called Nickelodeons) and were made by common people like them for common people like them. The theatrical elite meanwhile looked down their snooty noses at the growing Nickelodeons.

The Warner brothers started their movie career by buying a single projector and showing bootleg copies of films at carnivals. They made so much money that they packed in all their other enterprises and bought a movie theatre in Pennsylvania in 1903. Within a year, they had bought a second theatre. A year later, they set up a film distribution company and began to deal directly with film makers. When they saw how cheaply and quickly movies were being made, they decided to vertically integrate their business and not only show and distribute films, but make them as well.

The Warner brothers early success in the film business soon came to the attention of the Motion Picture Patents Company or MPPC. The Motion Pictures Patents Company was a shady trust set up by Thomas Edison, George Eastman and Thomas Kleine (owner of the biggest film distribution company at the time) to basically shut-down competitors. The goals of the trust were to legally (but not ethically) enforce the trio’s patents on film production and distribution. The upshot of which was that no one could use a film camera, projector or film stock without the approval of the MPPC. Not surprisingly, the MPPC approved Edison’s studios to make the films, George Eastman to supply the exclusive Eastman Kodak film stock and Kleine’s theatres as the only licensed distributor.

One of the big independent studios at the time, Biograph (home to D.W. Griffith, Mack Sennett, Lillian Gish, Lionel Barrymore and Mary Pickford), had been reluctantly welcomed in to the fold by the MPPC following a series of court battles that didn’t go the MPCC’s way. In 1910, Biograph director D.W. Griffith went to Los Angeles to make a series of short films including In Old California, the first movie shot in Hollywood. On returning to New York, Griffith told his Biograph bosses that California was a terrific place to make movies because of the cheap property, good sunlight and, most importantly, there was no harassment from MPPC goons. Biograph was reluctant to move from New York. However, other independent operators like the Warner brothers were mightily encouraged by Griffith’s praise of the place and decided to head West to check it out.

After a few scouting trips, the Warners decided to open a studio in Hollywood. In 1918, Warner Brothers Studios opened on Sunset Boulevard and hoped to crack it big with adaptations of Broadway plays. However, their big success came instead from a dog. Rin Tin Tin’s appearance in Where The North Begins started one of Hollywood’s earliest film franchises, spawning 27 films in total during the twenties and thirties.

Warner had mixed success in the twenties but in 1927, Warner released the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, which would establish the studio as the leader of the early talkies that were to take the world by storm.

Warner became the bad boys of the industry in the thirties with their gangster films starring James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson which earned the wrath of censors and the FBI for glamourising prohibition-era gangsters. The gangster pictures were so successful that Warner took over First National Pictures (who used to be as big as Warner in the twenties) and moved to bigger studios in Burbank.

The same anti-authority attitude of the gangster films could also be found in Warner’s Looney Tunes cartoons. Where Micky Mouse was law-abiding but cheeky, Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck took the law into their own hands and were raucous, rude and downright mean. These weren’t moral lessons for children or quality animation meticulously worked on for years like the Disney features. These were $3,000 shorts churned out every three weeks for a largely adult audience. Warner producer Ray Katz famously summarized the Looney Tunes ethos as “We don’t want quality and we don’t want it in the worst way”.

You could summarise Warner’s success in the 1940s with one name – Humphrey Bogart. When Bogart wasn’t making films, Warner wasn’t earning as much money. Bogart’s Casablanca was of course a watershed for Warner on both a critical and commercial level. Warner felt so indebted to Casablanca that it began using strains from its theme song As Time Goes By for its opening logo which can still be heard today at the opening of any Warner Brothers movie.

The fifties saw Warner find a new rebel in James Dean whose Rebel Without A Cause tapped the zeitgeist of emerging teenage angst. Sadly, Dean only made three films for Warner before dying in 1955 while driving his Porsche 550 Spyder which he had named “Little Bastard” and proved to be in the end when it slammed into a Ford Tudor in Cholame.

The sixties saw Warner create the environment for their own downfall as a studio by nurturing the auteur. Warners had cynically noted the growing appeal of the new French bad boys of La Nouvelle Vague (or The New Wave). Iconoclastic French directors like Jean-Luc Goddard and François Truffaut were challenging the way movies were being made in insisting that directors were artists and should be left alone to create. Warners thought they would give it a go by signing contracts with directors Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Penn which left them free of studio control. Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde was a return to form for Warner’s in being both a reinvention of their thirties gangster movies and as pioneering as their first talkie in ushering in a new era of director-led cinema. Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Robert Altman, Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese, Sydney Pollack, Francis Ford Coppola, Clint Eastwood (who has made all his films for Warner) and all the other directors that would flourish in the 1970s all owe their careers in some way to Bonnie and Clyde. It was the film that opened the doors to director-led cinema and the group of auteur directors that would become known as The New Hollywood. By the early seventies, the studio system of in-house directors, actors and production staff was all but over, replaced instead with film-based contracts and the lease of studio facilities to anyone who wanted them.

In 1972, the last Warner brother, Jack Warner, retired. In 1989, the company merged with Time Inc to become Time Warner, picking up DC comics as part of the deal. In the same year, Warner ushered in the still-current era of the gritty superhero franchise with the release of Tim Burton’s Batman. Now eclipsed by the Marvel franchises, Warner is in the process of striking back with a slew of superhero films based on DC comics scheduled for release over the next few years.

But the concept of the modern blockbuster franchise, arguably started with Star Wars, has had its most profitable home at Warner Brothers. In 2001, Warner would release the first films in the two biggest film franchises of recent times – The Fellowship of the Ring (under Warner subsidiary New Line Cinema) and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter films would go on to earn over $10 billion in box office earnings alone.

We had previously toured Warner Brothers Studios in 2001 and had enjoyed it. We still enjoyed it again in 2014 but found it to be more slicker and commercial than before with visitors shepherded towards curated exhibits more than working sets. Still, we did get to see a few TV shows that were shooting on the day we visited.

The Warner Brothers Staff Shop has been running for over 80 years, making bespoke architecture for movies and TV series.

A deserted street on the lot at Warner Brothers Studios. You will notice that the tops of the buildings aren’t completed. They don’t need to be as they are out of shot when filmed at street level.

The famous Friends set. A show about young couples in New York but made in a Hollywood studio. I was never a big Friends fan. I thought it was a cynical attempt to re-do Seinfeld but with beautiful and likable people. Seinfeld’s co-creator Larry David instructed writers that the Seinfeld should have “No hugs and no learning” whereas the opposite was true for Friends.

Harrie activates the Bat Signal. I know there are penalties for pranking emergency services but what about pranking Batman?

The next curated exhibit was the Harry Potter exhibit. Of course, the films were made at the Leavesden Studios in London but that didn’t stop costumes and props being shipped to Hollywood for this exhibit that tried to convince tourists that the films might have been made at Warner Brothers studios in Burbank.

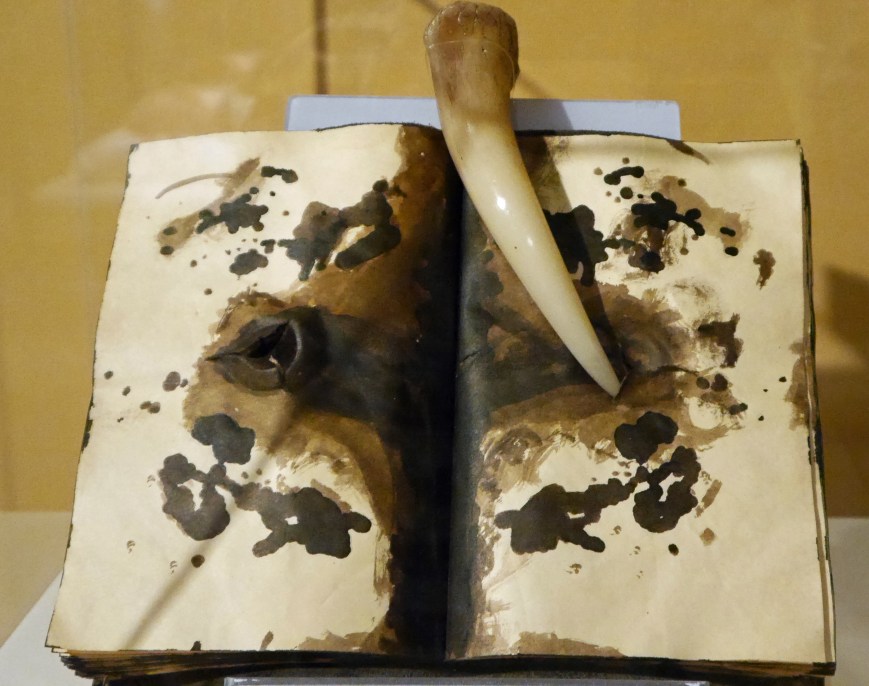

The ban on Weasley products by Dolores Umbridge. I used to have a boss who was just like Dolores Umbridge. I thought JK Rowling excellently captured a certain type of female executive who is cloyingly feminine and cutesy at a surface level while really being cruel and hard underneath and very much willing to do whatever is needed or asked for in order to maintain their position of authority.

Sorted By The Sorting Hat

Paramount Pictures

Next studio stop, the starry clouded mountain that is Paramount.

The story of Paramount Pictures is largely the story of Adolph Zukor, its founder and CEO for almost fifty years. Unlike the Warner Brothers and others who flocked to America at the end of the Nineteenth Century, Adolph Zukor never anglicised his name when he arrived in New York in 1889 as a young Jewish immigrant from Hungary. Zukor set about selling furs and did quite well out of it. Zukor became aware of the movie business when his cousin approached him for a loan to buy a nickelodeon parlor. Like the Warners, he could see the appeal of the movies to immigrant audiences but Zukor also saw that there was a gap in the market in making more respectable films for the middle classes.

In 1912, Zukor established the Famous Players Film Company with the aim to have “Famous Players in Famous Plays” and attract middle class audiences who thought the new motion pictures were too vulgar. Famous Players’ first film was a lavish French co-production about the loves of Queen Elizabeth the First starring Sarah Bernhardt who was then possibly the most well-known and respected theatrical actress of her day. The film was a great success and brought a new respectability to cinema that had been growing in Europe but was largely absent in America.

But making quality cinema wasn’t cheap and Zukor decided to hook up with the Broadway impresario and recent convert to motion pictures, Jesse L. Lasky. Lasky had just returned from Hollywood where he and his good friend Cecil B Demille had made Hollywood’s first feature film,The Squaw Man. The idea of a merger in order to make better movies sounded like a good idea to both Zukor and Lasky. But they also needed to lock in distribution, so Zukor approached William Hodkinson, the guy who opened the first American cinema (with a projection screen rather than lots of nickelodeon booths) in Utah in 1907 and who had gone on to become one of the leading West Coast film distributors. Hodkinson was interested in joining because he had a new business model that he wanted to try. His new model would become known as “block booking” and involved a system where in order for cinemas to take one film that they wanted, they also had to take a bundle of films that they didn’t want (much like Foxtel today). Zukor and Lasky loved the idea as it took away the headache of trying to sell films that were duds. In 1916, the trio formed Paramount Pictures where distribution of their films would indeed be paramount.

Paramount immediately went on an acquisition spree and started signing up popular entertainers in order to make them stars. After his early success with Sarah Bernhardt, Zukor became a strong believer in the power of a name to sell a film. This was at a time when movie stars were largely unknown. One of the more popular actors of the time was Mary Pickford but whose name was unknown to the general public. Moviegoers simply referred to her as “the girl with curls.” But it was Zukor who saw the potential of making Mary Pickford a household name by signing her up to Paramount and promoting her films using her name. It proved to be a great success and Zukor soon had a stable of bankable stars including Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Rudolph Valentino and Gloria Swanson. In fact, each signed star was represented in the Paramount logo which also featured a picture of a mountain in Utah where William Hodkinson lived.

Despite Pickford and Fairbanks splitting from Paramount to form their own United Artists studios, the twenties roared for Paramount as they carved out a reputation for quality pictures that also catered to what the public wanted (Zukor’s famous saying was “The public is never wrong”). Paramount stock was going through the roof as investors saw one smash hit after another culminating in the blockbuster Wings that also won Best Film at the first Academy Awards in 1928.

The following year, the Great Depression hit and Paramount stock took a bath. Five years later, the company was bankrupt. Zukor convinced the receivers that he could trade his way out of bankruptcy and turn around Paramount’s fortunes. The way he did this was to hire more stars (The Marx Brothers, Gary Cooper, Carole Lombard, WC Fields, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West, Claudette Colbert, and Bing Crosby being among the new Paramount stable) and push the block booking system hard. Movie theatres now had to take even more dross in order to get Paramount’s desirable pictures which meant that Paramount could subsidize their “A” pictures with cheap “B” features but charge the same for both. Zukor also came up with the idea of “pre-selling” hot films yet to be made. Theatre owners had to pay upfront to secure these films or else they stood the risk of losing distribution to their competitors.

While this was good business for Paramount, the theatre chains hated it and started complaining to the US Justice Department. The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission started looking in to things and didn’t like what they found. After many legal skirmishes, the matter was finally settled in the US Supreme Court in 1948 where the court struck down Zukor’s integrated model of block booking and pre-selling. In fact they went further and stipulated that movie studios could not also own movie theatres.

Zukor was not happy with the decision but shrugged it off and decided to apply his old vertically-integrated model to the the emerging television industry. Zukor could see a new business model emerging and said at the time “rather than lose the public because television is here, wouldn’t it be smart to adopt television as our instrument?” So Zukor started buying up television stations to take Paramount content and also bought a stake in American television manufacturer DuMont. But before Zukor could start rubbing his hands in anti-trust glee, the Federal Communications Commission stepped in to investigate what this inveterate fixer was up to. Like the Justice Department before them, they didn’t like what they saw and quickly busted up Zukor’s new television racket.

After that, Zukor decided it was time to retire and stood down as Chairman in 1959. This left the company directionless and uncertain of its future. Paramount was eventually bought out by corporate conglomerate Gulf and Western whose owner Charles Bluhdorn had a similar background to Zukor in being a European Jew who knew how to give the public what it wanted. Bluhdorn thought that Paramount needed to get with the times and hired bad-boy producer Robert Evans (his autobiography The Kid Stays in the Picture is a hoot) to shake things up. Evans got Paramount back on track with critical and commercial hits including The Odd Couple, Love Story, The Godfather, Three Days of the Condor, Chinatown, and Rosemary’s Baby.

Paramount continued its reputation for quality commercial films combined with star power with the Indiana Jones franchise and with popular films by Eddie Murphy in the eighties and nineties. Paramount also did nicely out of a deal during this period with Twentieth Century Fox to co-fund James Cameron’s blockbuster Titanic.

In the 2000s, Paramount realised that it was being left behind in making animation films that were proving popular with family audiences. After a few failures, it decided to buy Dreamworks outright for $1.6 billion so that it could compete with its rivals Disney and Pixar. More recently, Paramount has had great commercial success with its critically unsuccessful Transformers movies.

At the beginning of our tour of Paramount, the tour guide led us down a corridor of pictures from famous movies. When she got to the last picture of a scene from Transformers, she lowered her voice and said “The director Michael Bay walked down here and was really angry one of his films wasn’t included in Paramount’s classic film gallery. So, because the films make so much money for Paramount they had to give in to him and put up a picture from Transformers.” She lowered her voice even softer and continued “It’s hardly a classic film is it though?”

The tour itself was almost identical to the one we had done back in 2001 and was quite old-fashioned in contrast to the other studio tours on offer. The tour guides are actually interns at Paramount and have to do the tour as part of their job. This meant that they knew quite a bit about what was going on in the studio and while Paramount might have concerns about what they might say, I appreciated our guide’s candor and insights.

Standing in front of the famous Paramount Gate. The same one Gloria Swanson and Erich Von Stroheim drive through in Sunset Boulevard.

This is the Paramount parking lot that also converts into a water set. When we were here in 2001, they had just shot Castaway on it.

Sony Pictures Studios

For our third studio, we headed to Sonī Kabushiki Gaisha Sutajio or as the locals call it, Sony Pictures Studios.

It is hard to know where to start in describing the disjointed history of the parcel of land that now goes by the name of Sony Pictures Studios. Perhaps the beginning is a good place to start when in 1912 silent film director Thomas Ince (see my previous post about Ince’s strange death aboard William Randolph Hearst’s yacht) set up Inceville in the Santa Monica hills. Inceville was the model for how the studio system would work for the next fifty years. While there were many film “studios” around at the time, they were generally large lots where films sets would be constructed for each film. Inceville was less a film set and more like a factory. Inceville had permanent indoor and outdoor sets for popular settings (a Western town, a European village, a pirate ship and, somehow appropriate given Sony’s recent ownership, a Japanese village were among the sets), a full-time commissary to feed staff, a props department, a wardrobe department and a new production-line approach to making movies. Before Inceville, the director and cameraman generally controlled a movie. After Inceville, it was the producer who called the shots in appointing salaried staff (directors, cameramen, actors, editors etc) to specific films. It would become the model for all Hollywood Studios up until the late sixties.

In 1915, real estate hustler Harry Culver started wooing Hollywood types to set up shop in his newly acquired land purchase that he modestly named Culver City. Thomas Ince was interested as it was closer to the heart of Hollywood as was director D.W. Griffith who had just left Biograph to set up the Mutual Film Company with his business partner Harry Aitken. So what do good real estate agents do when they have competing bidders. Pit them against each other of course. Culver told Ince about the interest from Griffith and also that he had been talking to Mack Sennett (of Keystone Films and Keystone Cops fame). But instead of entering a bidding war, Ince, Griffith and Sennett banded together to form the Triangle Film Corporation and purchased the land as a joint venture.

In 1915, Ince moved Inceville to the new Triangle Film Studio lot in Culver City (the lot now occupied by Sony Studios). Here Ince made epic films such as Civilization which performed well at the box office. But big as it was, the new lot just wasn’t big enough for director D.W, Griffith who needed a larger block of land to recreate ancient Babylonia for his epic follow-up to Birth of A Nation called Intolerance. With expensive sets and over 3,000 extras, Intolerance became the most expensive movie ever released up to that point when it was released in 1916. Back in the teens, the average cost of making a movie was around $15,000. Intolerance cost $2.5 million to make (the equivalent of 208 movies). However, Intolerance also suffered the ignominy of being the most expensive flop up to that point as well. Triangle took a big financial hit.

Around this time, the brother-in-law of Jesse Lasky, Samuel Goldfish (born Szmuel Gelbfisz in Poland), was getting restless. Working at Paramount, he hated Paramount Studio boss Adolph Zukor and thought he could run a better studio himself. This ambition was realised when he met Broadway producers Edgar and Archibald Selwyn who were keen to enter the slowly-becoming-more-respectable film business. Goldfish and the Selwyns formed a new company called Goldwyn Pictures and set about wooing investors. They soon got their money and started renting facilities in Hollywood (first at Solax Studios and then on the Universal lot). Seeing the inverse relationship between the profits of Triangle Films and the costs of their expensive studios, Goldwyn approached Triangle to buy them out. Needing the money, Triangle management agreed and in 1918, Goldwyn Pictures set up shop in the Triangle Film Studio in Culver City. Goldfish had hit the big time and could now stick it up Adolph Zukor and Paramount. To show off his success, he changed his much-mocked surname from Goldfish to Goldwyn.

Goldwyn Pictures had lots of early successes but Samuel Goldwyn’s cantankerous personality rubbed a lot of people up the wrong way. Goldwyn basically didn’t like or trust working with others and wanted to micro-manage all aspects of his productions. In 1922, his investors and partners had had enough and forced him out of the company.

In 1924, successful theatre-chain owner Marcus Loew, bought Goldwyn Pictures in an attempt to sure up his ailing Metro Pictures company which had achieved limited financial success despite Loews Theatres pushing their films hard. However, Loew wasn’t that impressed with the management at Goldwyn Pictures and wanted someone better to oversee operations. He approached Lois Bert Mayer (formerly Russian Jew, Lazar Meir) who had established himself as a successful producer for a number of studios. Mayer agreed and in 1924, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was formed.

With Loew’s big theatre holdings, MGM was keen to duplicate Paramount’s vertically-integrated model and focus on quality films that they could charge more for. “Boy Wonder” producer Irving Thalberg was put in charge of production and the studio adopted the motto “Ars Gratia Artis” (“Art for art’s sake”) to signal its intention to go toe to toe with Paramount.

This all went according to plan until Marcus Loew unexpectedly died of a heart attack in 1927. Equally unexpected was the acquisition of Loew’s theatre holdings by William Fox of Fox Films fame. Louis B. Mayer hated the idea of working with someone who was already running a competing studio. Mayer used his political connections in the Republican Party to have the Department of Justice investigate the acquisition on anti-trust grounds (although it was seemingly alright for MGM to engage in anti-trust activities when Loew was alive). Mayer needn’t have worried, as the following year, the stock market crash ruined Fox and the deal never went through.

The twenties roared as loud as MGM’s mascot Leo the Lion. MGM released the popular Buster Keaton films, big budget epics such as Ben Hur and the early technicolor hit, The Black Pirate with Douglas Fairbanks. The old Triangle Studios’ lot proved to be a great place to make pictures and MGM began releasing over 100 films a year.

However, the talkies craze caught MGM by surprise and MGM was one of the last studios to convert completely to sound in the early thirties. By then, MGM’s productions had dropped to less than 50 films a year. MGM’s star factory backed a winner when it signed up Clark Gable in the mid-thirties. Gable’s success for MGM continued in 1939 when Louis B. Mayer’s son-in-law, David O. Selznick, produced Gone With The Wind featuring Gable at his smoldering best. 1939 was a golden year for MGM as they released The Wizard of Oz, Goodbye Mr Chips and Ninotchka to popular and critical success. Mind you, they also released the troubling Tarzan Finds a Son! in the same year where Tarzan (Johnny Weissmuller) finds a child survivor from a plane crash and adopts him as his son naming him “Boy” and then when Boy’s relatives arrive to search for him, Tarzan lies and tells them that the child died in the plane crash.

In the forties, MGM fell on hard times. The death of Irving Thalberg in 1936 and Louis B. Mayer’s increasing search for, and reliance on, wunderkind producers like David O. Selznick (they were dubbed “The College of Cardinals” by MGM insiders) contributed to a growing creative vacuum within the studio. By the end of the forties, MGM was producing less than 25 films a year; a quarter of their output from the twenties. Pressure was put on Louis B. Mayer to resign and let someone new take over and in 1951, Louis B. Mayer succumbed.

Mayer was replaced by RKO producer Dore Schary who arrived just as the Justice Department were pursuing Paramount over their anti-trust activities. When the Justice Department won the case, they turned their sights to MGM and forced MGM to separate from Loews Theatres. On the ropes, MGM rolled the dice on one last epic to restore their flagging fortunes. That epic was the remake of Ben Hur which went on to win 11 Academy Awards (out of 12 nominations) and become the highest grossing film of 1959.

Ben Hur became the new business model for MGM with the studio putting all its eggs in one basket for a blockbuster film every year. This largely worked with King of Kings, Mutiny on the Bounty, How The West Was Won, Doctor Zhivago, The Dirty Dozen and 2001: A Space Odyssey all proving big hits.

In 1969, Las Vegas mogul and Caesar’s Palace owner, Kirk Kerkorian, bought a 40% controlling interest in MGM and announced to the press that MGM was going to become a hotel company. Kerkorian slashed film output to five films a year and sold off 40 acres of the studio for real estate. In the meantime, he started building MGM-branded casinos across country.

In 1981, Kerkorian bought United Artists and merged the two studios to create MGM/UA. In 1986, he sold MGM/UA to Ted Turner who primarily wanted the studio for its old film library. But the debt incurred from the purchase proved too much for Turner who was forced to sell MGM back to Kerkorian only five months later. Kerkorian then struck a deal with Lorimar TV productions to buy the Culver City lot and the old Triangle lot now had a new owner. Lorimar removed the MGM logo and set about making TV shows at their new studio.

In 1989, Warner Brothers bought Lorimar. In the same year, Sony purchased Columbia Pictures and did a deal with Warner Brothers to purchase the Lorimar lot in order to have their own working studios. Sony then spent $100 million on renovating the by now run-down lot.

Meanwhile, poor old MGM was sold once again to flamboyant Italian financier Giancarlo Parretti in 1990. The story of Parretti’s time at MGM was famously parodied in the book and film Get Shorty which bizarrely was released by MGM when Parretti was still boss. Parretti’s first order of business at MGM was to fire all the accounting staff and appoint his 21 year old daughter as the senior financial director. This allowed him to raid MGM’s coffers to lead an excessive lifestyle in Hollywood with his “harem” (Parretti’s words) of young women who were listed on the MGM payroll as “actresses.” California Superior Court Judge Irving Shimer would later observe that Parretti and the banks that backed him weren’t “interested in making movies. They were interested in getting girls on the yacht…That’s why bankers come to Hollywood -lots and lots of pretty girls.”

In 1991, Parretti was charged with fraud in both the USA and Europe and the company was sold back to Kirk Kerkorian who bought the studio for the third time. But Kerkorian would once again sell off MGM; this time in 2005 to Sony Entertainment. Meanwhile, Kekorian would continue to build his MGM resorts empire which today makes over $10 billion in revenue and include the majority of big casinos on the Las Vegas strip (Bellagio, The Mirage, Luxor, Mandalay Bay,

MGM Grand, New York-New York, Excalibur, Circus Circus and six smaller casinos).

So through circuitous dealings, Sony had ended up with both the old MGM lot and the MGM company. But MGM’s debt from the Parretti years and its ailing commercial fortunes were too much for Sony and MGM declared bankruptcy in 2010. The company has since successfully traded its way out of bankruptcy and is on its way to becoming a fully listed public company. It has also reacquired United Artists (which was partly sold to Tom Cruise in 2006) and has appointed Survivor and Apprentice creator Mark Burnett as the CEO of the new United Artists Media Group.

We visited the Sony lot back in 2001 and thought it was the newest looking studio at the time due to its extensive renovations. We were amazed to see that even more renovations had taken place since our last visit and reflected on the recent leaked emails of the extravagance that goes on at Sony/Columbia pictures. Nowhere was this most evident than at the Happy Gilmore production offices on the lot where we saw Adam Sandler’s pimped-up golf cart and were told of his expensive demands. Why is the studio so keen to keep a b-grader like Adam Sandler anyway we thought? Surely, his star is on the descendant?

The tour was okay but a bit too slick and light on in showing us any real treasures. The twenty minutes visiting the set of the game show Jeopardy might have been appealing to American couch potatoes but we couldn’t have cared less.

Sony Pictures Studios. Formerly Lorrimar TV Studios, MGM Studios and Triangle Film Studios. Note the 29 metre tall rainbow that pays tribute to MGM’s “Wizard Of Oz” which was shot here.

The RV from “Breaking Bad.” Having taken a ride in its replica in Albuquerque, we felt right at home.

The Hollywood Museum

Situated in the old Max Factor Building, The Hollywood Museum is the so-called “official” museum of Hollywood and features four floors of exhibits. It is a terrific mix of polished and amateurish exhibits from all eras of Hollywood film and TV. Harrie and I had a great time checking out all the exhibits while Michelle relaxed back at the hotel.

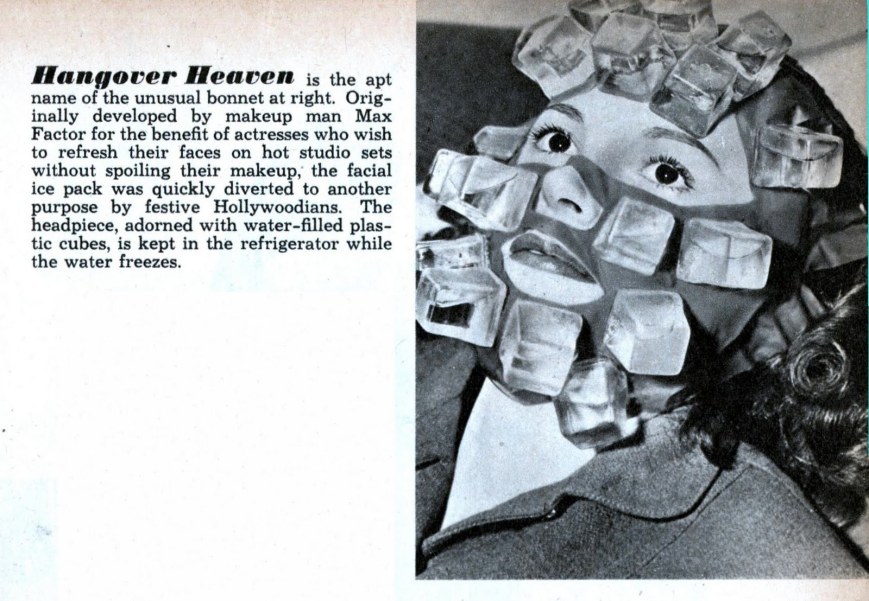

Given that it is in the Max Factor building, there are some great exhibits on Factor’s pioneering work in making actor’s kissers look good. Harrie was even interested in the man who popularised make-up. And it is a good story too as Polish Jew, Maksymilian Faktorowicz (later anglicized to Max Factor), single-handedly created the glamour make-up industry from very humble beginnings.

Back in the early twentieth century, lip rouge and greasepaint was something only reserved for theatrical actors. Outside of the theatre, it was seen as licentious and was only used by prostitutes (“painted ladies”). When Max Factor came to Hollywood to set up a wig shop for film actors, he saw a problem. His wigs worked fine in the movies but he thought that the theatrical greasepaint (so-called because it was largely made out of lard) used by the actors was more suited to the theatre than to film. This was because it looked fake and rigid in film close-ups which was never a problem with the theatre where audiences sat far away from the actors. Factor set about creating a more naturalistic and flexible greasepaint that used creme as its base and came in twelve different shades to suit different skin types. Of course, face creme wasn’t new even back then. Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubinstein had educated a generation of women about the importance of “skin care” and sold cremes and various ungents to keep the skin looking clean and fresh. But what Factor came up with was something different. This was about fooling people that your skin looked smooth and lustrous even if it wasn’t. This was about glamour, the cosmetic version of acting.

It wasn’t long before all of Hollywood turned to Factor to make their kissers look good. He invented the first lip gloss (Lip Pomade) that allowed actresses to have shiny lips without having to lick them just prior to filming like they had previously done. He invented the “heart shaped” lip for Clara Bow (the precursor to the bee-stung lip) and the “smear” for Joan Crawford. When Technicolor came in, he invented Pan-Cake or what would become known as foundation to soften shiny faces and mask skin imperfections. He invented Color Harmony, the principle that certain combinations of make-up work best on certain face types and complexions; a method still used today. And he invented liquid nail enamel, a fore-runner to the modern nail polish.

But not only did Max Factor revolutionize glamour make-up, he revolutionized its distribution as well. Unlike Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubenstein who sold their wares through their own shops or in up-market department stores, Factor wanted his make-up to be accessible to every woman in America. He hit upon the idea of distributing it through chemists and trained chemist workers on how to apply make-up so that they could give demonstrations in their stores. It seems strange now, but back then women had to be taught how to apply this new makeup and shown its benefits.

As for being sold on its benefits, here again Factor blazed the trail for modern celebrity advertising. Famous name actresses of the day were paid one dollar to advertise Factor’s products in return for a mention of their latest movie in the Max Factor ad. Women who wanted to look like these actresses in these films rushed to their local chemist to buy the make-up advertised. Of course, these days, such celebrity endorsement comes at a much higher price than the one dollar paid to the 20th Century’s “It” girl Clara Bow when she promoted Max Factor. The 21st Century’s “It” girl Beyonce gets paid $5 million to endorse L’Oréal cosmetics.

Not the mask from the guy in Hellraiser but Max Factor’s Beauty Calibrator. The plaque shows how it works.

A Max Factor advertisement from 1931 explaining why actresses look so good on the screen. Women also had to be trained in how to use this new “make up”and could either attend a training session at their local chemist or send away for a free book.

A celebrity endorsement ad with Merle Oberon. Max Factor pioneered the actress celebrity endorsement advertisement in the twenties. By the fifties it was ubiquitous around the world.

Not a B-grade Zombie movie but a shot of what the actors looked like off screen in the early days of television. Max Factor Jr (Max’s son) adapted his father’s panchromatic make-up to compensate for the fact that the early television cameras were highly sensitive to colour and didn’t record the colour red and so left the face looking flat and featureless. To bring back the features, Factor Jr would substitute normal makeup for a combination of blue and green makeup. In the picture above, the dark parts around the eyes and cheeks are green, while the lips and upper eyes (where mascara would be applied) are blue.

The Hollywood Museum has some great artifacts from the silent era including this case devoted to Wings.

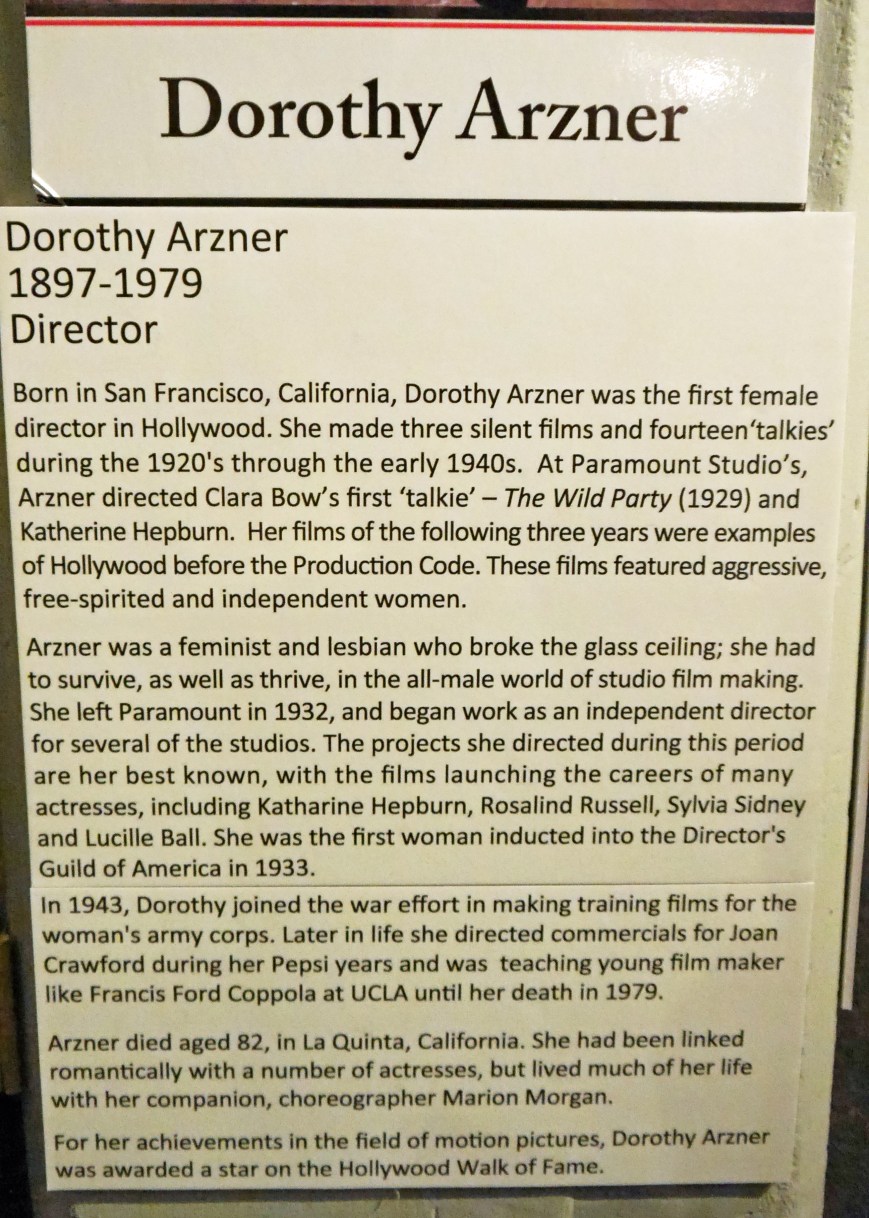

Dorothy Arzner, Hollywood’s first female director (also the world’s first lesbian director), directing her 1927 film Get Your Man. The world’s first female director was French director Alice Guy-Blaché who directed her first film in 1896.

The original studio sign and camera from Hal Roach Studios, home to Laurel and Hardy, Our Gang, Harry Langdon, Will Rogers and many other funny guys.

The miniature of the fire escape stunt in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Check it out here.

Before Elizabeth Taylor’s expensive version of Cleopatra, there was Theda Bara’s expensive version of Cleopatra. And going by the leaked Sony emails, it looks like Angelina Jolie harbors a desire to do her own expensive version. When people talk about screen “vamps”they refer back to Theda Bara, the original screen femme fatale who earned the nickname “The Vamp” because she looked like a seductive vampire.

The purple pulchritudinous dress of Joan Harris (Christina Hendricks) from Mad Men. Full-figured doesn’t even remotely capture it.

La Brea Tar Pits

Having enjoyed seeing the old Hollywood, we next visited the really old Hollywood. Specifically, the Pleistocene era where, like today, Hollywood mammals got themselves into sticky situations and sunk into obscurity.

I had previously visited La Brea Tar Pits back in 1978 when we went on our big overseas vacation. To me, it had the fading memory of an an old Seventies Viewmaster reel. Lots of washed-out colours and certain cheesiness. Coming back again, 36 years later, I found that it was almost completely the same. Also, now having a slightly better grasp of Spanish, I realised that The La Brea Tar Pits actually translates as “The The Tar Tar Pits”.

The George C. Page Museum (named after the Californian real estate developer who funded the place) is still small and a bit tired with fading brown exhibits and old painted backdrops. We went on a guided tour which was worth it to see the archaeological work still taking place at this site. The ground around Hancock Park still bubbles and oozes a mixture of crude oil and gilsonite (colloquially known as tar) which gives it a life the museum somewhat lacks.

It all started back in the late 1800s, when the Hancock family noticed that strange brown bones were emerging from the tar pits at the edge of their Ranch La Brea in Los Angeles. It wasn’t long before paleontologists began flocking to the place to unearth (or should that be to untar) fully preserved skeletons of the mega fauna of the Pleistocene era. The family eventually agreed to deed the land to the Los Angeles County Museum where since 1913, excavations have continued in earnest.

While the Page museum was somewhat underwhelming compared to the many other museums we had visited on our trip, it was worth it to witness one of the funniest pieces of tourist commentary I had ever heard. One of the people on our tour was a doddery old-timer whose face was obscured by a large baggy cap with the US flag on it. He was accompanied by his overweight wife who also looked quite frail. They both shuffled around to each exhibit, dutifully listening to the tour guide and not saying a word. However, when they came to a giant skeleton of a mammoth, the old timer let out a low whistle and, in a loud voice that belied his frail body, yelled “Would ya get a load of this big gorilla!”

Harrie transfixed in a tar-like gaze at his iPod outside the George C Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits.

The bubbling tar pits where fake elephant statues are placed. I still have vivid memories of these elephant statues with their wild eyes from my previous visit here back in 1978.

This is the giant mammoth exhibit which provoked the exclamatory cry of “would ya get a load of this big gorilla!”from an otherwise sedate tourist.

This faded painting was also one of my previous recollections of the place. Most of the older exhibits have paintings like these as back drops.

Santa Monica

We took an Uber ride to Santa Monica where we last stayed on our honeymoon in 2000. We headed straight to Santa Monica pier to kind of cheat on our claim to have reached the end of Route 66 (we skipped the California route). When we reached the “End of Route” sign, we encountered a group of bikers wearing the same t-shirts. It turned out that they were all cancer victims and who had done the route for real. We talked to them about where they had been and stayed awhile to take their photos while they returned the favour by taking ours.

We then headed to the amusement arcade where Michelle was spurned last time for coming up with a “system” to beat the odds on one of the prize giving machines. At that time, Michelle attracted a big crowd who stood around to see her roll quarters down a chute and hit a dump truck target with every coin while hundreds of prize tickets kept streaming out of the machine. Those in charge of the place eventually gathered and gave her a suspicious look. Eventually, Michelle stopped and an “Out of Order” sign was quickly placed on the machine. When we returned this time, Michelle was over-joyed to find the same machine and started back on perfecting her system. You can see the results in the video below.

Michelle’s System

The Last Stop Shop on Santa Monica Pier with its tribute to Bob Waldmire whose hand-drawn maps guided us along Route 66.

Returning ,still happily married, after our 2000 honeymoon at the beautiful Art Deco Georgian Hotel in Santa Monica. We used to have breakfast in the hotel’s former speakeasy.

Not the New Jersey amusement park of the Freddy “Boom Boom”Cannon song (incidentally written by the Gong Show’s Chuck Barris) but the 1.5 boardwalk park along Santa Monica beach.

The Streets of Hollywood

Out and about on the streets of Hollyweird.

Standing outside Grauman’s Chines Theatre. The theatre is now owned by Tron producer Donald Kushner and Lebanese film financier Elie Samaha.

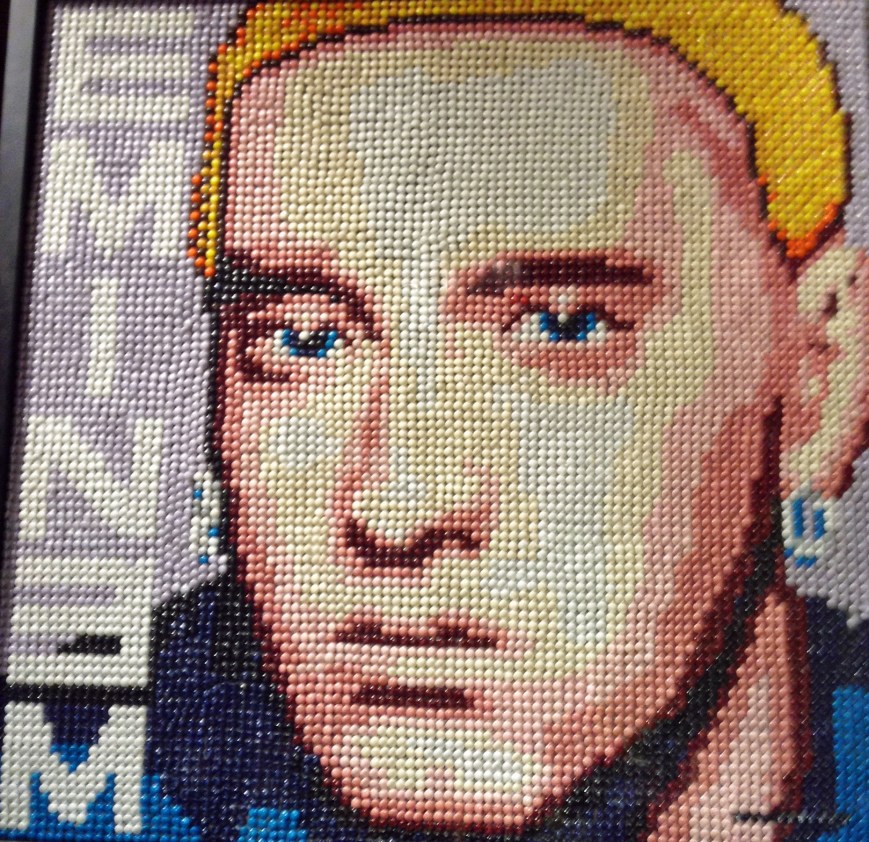

A portrait of Eminem made entirely with M&Ms at Sweet, the giant confectionery shop on Hollywood Boulevard.

One of my favourite record shops in the world – the incomparable Amoeba Music. It is a giant two-storey warehouse full of vinyl and polycarbonate plastic wonders. I brought home half a suitcase full of old and new stuff that cost me about a hundred bucks.

Joining the queue outside of Pink’s hot dogs on North La Brea Avenue. Pink’s has had many celebrity encounters since it first opened in 1939. Testament of this can be seen on its walls which are covered with in-store celebrity photos dating back to the Forties.

Harrie decides whether to take on Pink’s Three Dog Night – three 12 inch hot dogs with cheese, bacon and chili in a single bun.

Walking down La Brea Avenue, our eyes were blinded by the reflection from a giant silver object in the distance. Imagine our surprise as we got closer to find that it was Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov or the Bolshevik formally known as Lenin; a man who had once promised to “encircle that last bastion of capitalism, The United States of America… as it is inconceivable that Communism and capitalism can exist side by side. Inevitably one must perish.” So, not a great enthusiast for the Amercian Dream. But that’s Post Modernist art for you. “Miss Mao Trying to Poise Herself at the Top of Lenin’s Head” by Chinese artists, The Gao Brothers.

Pity the poor person who has to work in the Smokin’ Shack. I think this has to be the smallest drive thru ever.

The Hollywood and Highland Center on Hollywood Boulevard which draws its inspiration from the Babylonia scenes from D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance.

Here is a picture of the original set from Intolerance (1916). Of course, this was created using the old CGI – Carpenter Generated Imagery.

We were amazed to finds a giant cement factory only blocks away from Hollywood Boulevard. Grauman’s Chinese Theatre can’t require that much of the stuff can they?

When we were last here in 2001, there was nothing commemorating this site. I remember peering through the iron gates and checking that we had the right place on our maps. It is good to see the Cultural Heritage Commission has put up landmark plaques around town.

Lunch in the Hollywood Hills

Before setting off on our big American adventure, I was encouraged by my uncle to meet with my cousin Trent who was working in Hollywood and living in the Hollywood Hills. I hadn’t seen Trent since he was teenager and our families didn’t really keep in contact very much. Trent had very kindly invited us to lunch at his place on Sunday and Harrie was really keen to meet his two second cousins as they qualified in not being adults. I was a bit apprehensive about meeting Trent given that we hadn’t spoken for eons and also because of his insanely busy work schedule that we were quite literally eating into with Sunday lunch.

Trent and his wife Sarah were great hosts and we had a nice Sunday sitting by the pool drinking and hearing stories about P22, the famous mountain lion that roams the Hollywood Hills (check out its Facebook page). Actor Damon Herriman came over in the afternoon and very kindly gave us a lift to The Hollywood Bowl after our Uber ride failed to turn up. It was a nice, and very down-to-earth, combination of family, fame and food.

Harrie and his two second cousins beneath the Hollywood sign and on top of old Smokey all covered in fur, of course I’m referring to Smokey the Bear (to quote from Alan Sherman).

The Simpsons

Having watched all 574 episodes of The Simpsons, we considered ourselves to be fans of the show – even by The Comic Book Guy’s standard. So it was with great surprise and even greater delight that we got to meet the cast and see them perform.

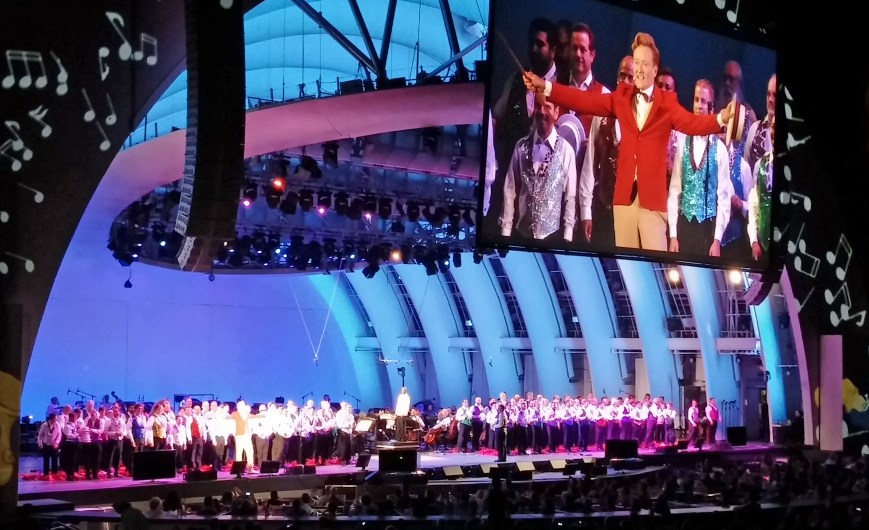

The first time we saw them perform was on stage as part of the 25th Anniversary Concert at the Hollywood Bowl. It was a beautiful balmy night as we walked to our seats in the classic Twenties outdoor ampitheatre. There was a real sense of reverence and awe in being “live” in the home to so many classic “Live at the Hollywood Bowl” concerts. The previous week, old talkbox rocker Peter Frampton had performed his Frampton Comes Alive! album at the Bowl and the crowd certainly came “Alive!” again at the first strains of the Simpsons theme song. This was a big love-in for the fans but the performers didn’t take it for granted and delivered a very funny and energetic evening which even included a fireworks finale. Matt Groening and most of the cast were there with the noted absence of Harry Shearer, Dan Castellaneta and the notoriously shy Julie Kavner. The guests included Weird Al Yankovic, Conan O’Brien, Beverly D’Angelo, Jon Lovitz, Hans Zimmer, and the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles (who did an awesome version of “Spider Pig”).

But as Simpsontastic as that was, it was topped by Trent getting us tickets to a cast table reading of a Simpsons’ episode at Fox Studios.

Fox studios is what remains of the giant 176 acre Twentieth Century Fox lot that used to take in what is now the upmarket Century City shopping mall. Walking through this highly urbanised area, it was hard to believe that this was once Western star Tom Mix’s ranch before being sold to William Fox in 1928. The studio is not open for public tours, so we were very lucky to be given a private tour by Trent who took us on a golf buggy around the different lots where we saw TV shows being filmed. Trent was very kind with his time given that his time was being demanded left, right and centre from his work colleagues while we were there. We were all impressed at how calmly and confidently he handled everything.

We got to sit on set and see a scene of New Girl being shot which was pretty cool. The sets for the show were amazing and I was impressed at the way the actors stayed fresh after multiple takes. Harrie was excited to see Damon Wayans Jr and Jake Johnson who we had seen the previous week in Let’s Be Cops at the drive-in in Santa Barbara.

But the highlight of our visit was sitting down in a room with The Simpsons‘ cast, writers and producers. When we arrived, we were given a copy of the script (the episode was called “Cue Detective”) and were ushered to a row of chairs that were placed against the wall. Then one by one, Simpson’s cast members began arriving and started chatting. Matt Groening and James L. Brooks introduced a brief discussion on the previous evening’s concert at the Hollywood Bowl and it was interesting to hear how the performers thought it went. After this, Joe H. Cohen started talking about the script he had written for the episode. A new character was explained to Hank Azaria who tried a number of voices to see which one worked best. Then the cast proceeded to have a read through of the script in character.

It was amazing to see the actors produce character voices that seemed totally removed from their physical appearance. Somehow a young Bart sprung from the lips of the middle-aged Nancy Cartwright and after Dan Castellaneta tucked his chin into his chest, his normal voice became the slow ponderous drawl of Homer Simpson. Hank Azaria (Moe, Chief Wiggum, Apu and many more) was very versatile at switching from one character to another and in effect talking to himself for whole scenes.

Everyone seemed to get on well with one another and there was a lot of laughing. The read-through was often broken up with side discussions about certain popular culture references in the episode and there was lots of riffing off various lines. It was clear that everyone was pretty relaxed with one another after working together for 27 years. The episode itself was very funny and we looked forward to seeing how it would end up as a finished product.

After the read-through, we got to talk to Dan Castellanetta, Yeardley Smith, Nancy Cartwright, David Silverman (the original animator of the Simpsons shorts and director of The Simpsons Movie) and Chris Edgerly who was standing in for Harry Shearer. All were very nice and signed copies of our script as well as a giant Simpsons poster that now sits framed on our wall at home.

This was an amazing end to our trip. We were all very grateful to Trent for arranging such a great finale to our last day in America.

Former Simpsons writer Conan O’Brien makes a guest appearance as Monorail promoter Lyle Lanley from the episode Marge Vs The Monorail that was also written by O’Brien.

The Simpsons Take The Bowl

Harrie and Michelle with signed Simpsons scripts in hand at Fox Studios.

Homeward Bound

We walked from Fox Studios to the swanky Century City Mall where we did some last minute shopping before heading to the airport. It wasn’t until we were sitting in the airport departure lounge that it both sadly and relievedly dawned on us that, after 80 days of travelling, our trip was over. The large Qantas plane that we could see outside the dirty glass window was there to take us home. It was late when we boarded and we had no trouble drifting off to sleep as we hurtled home at jet speed.

This great homage to the Silent era is featured in one of the open areas in LAX

Harrie’s snaps the Sydney Airport welcome sign on his iPod to alert his Instagram followers that he is home.